Africa’s mobile revolution is a trending topic on the continent’s ever-swelling wave of cellphone use and multi-sector apps. But is it an actual revolution that’s driving real social change? Or is it just tech-happy hype and, if so,

what does this mean for Africa’s future?

It took 10 years for The Economist to eat its words about Africa. In May 2000, the cover of the magazine blatantly called it “The hopeless continent”. But with six of the 10 fastest-growing nations of the last decade located in Africa, the continent answered back and assured everyone that it’s not hopeless, but healthy and on the rise. The Economist responded in December 2011 with the cover line “Africa rising”. And the continent continues to rise in many ways– as does its number of mobile phones.

This has led to a continued frenzy of Africa orientated apps for everything from mobile banking and education to crowd-sourcing and health-system support. Some have worked better than others, but still the app obsession continues undeterred.

Perhaps it’s time to investigate which mobile developments are successfully innovating and adding to Africa’s rise. Perhaps it’s time to see if all this mobilisation is really worth it after all.

More people with more money

Africa’s rising has mainly been driven by (notoriously fickle) commodity prices. But there has also been a simultaneous increase in the purchasing power of many households, meaning more demand for more consumer goods.

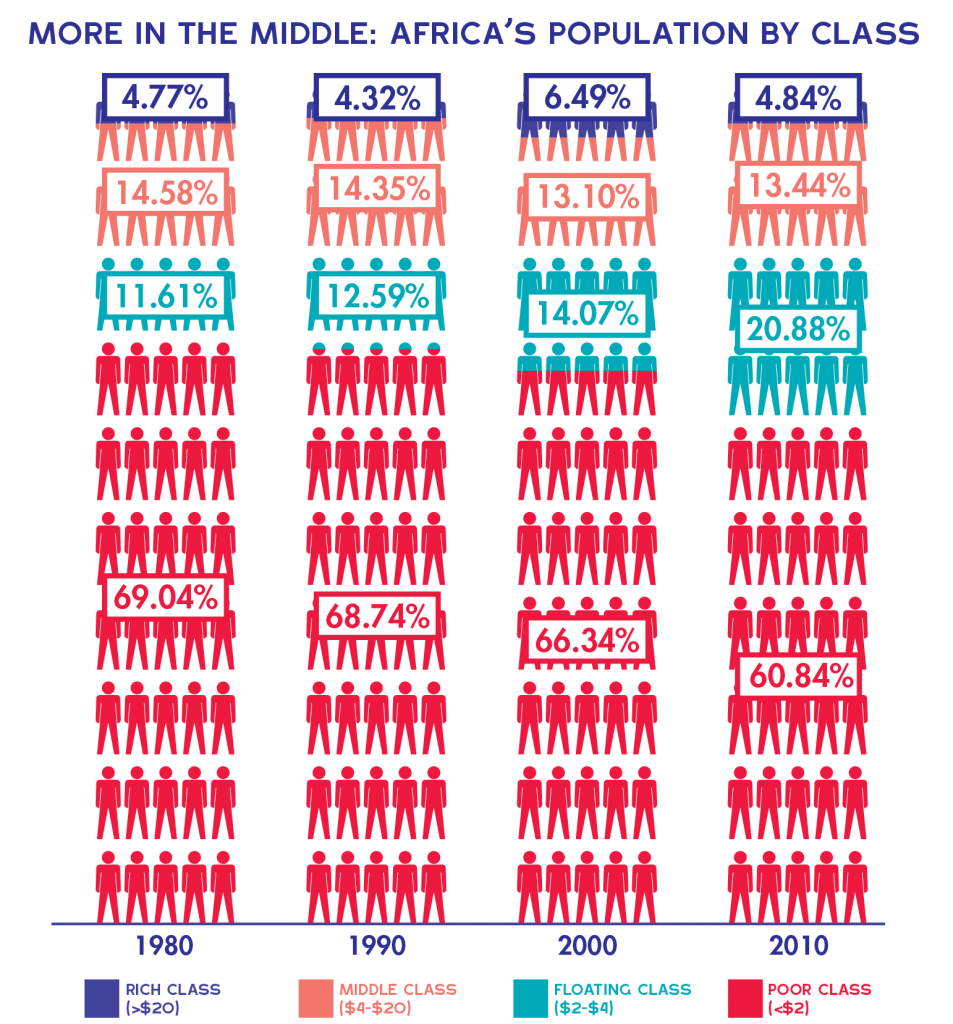

By 2010, the African Development Bank (AfDB) found that Africa’s middle class had risen to 34%of the population. That’s 350-million people –roughly one in three Africans – 180-million of whom were securely enough in the middle class to face less risk of slipping back into poverty in the event of exogenous shocks.

Mobile operators go for the middle

Despite the continent’s growing consumer class, many companies were slow to respond to the growing demands. But not the mobile operators. These fast-moving exceptions managed to spot the potential and secure sizeable chunks of the market – in particular, certain Africa-based operators like South Africa’s MTN and Vodacom, and Nigeria’s Glow.

Indeed, Africa’s strong middle class emergence is mirrored by a rapid increase in mobile phone penetration. How rapid? Well, rapid enough to go from a relatively negligible number of connections and subscribers in 2000 to nearly1-billion connections and an estimated 735-millionsubscribers by the end of 2012 (according to the Research and Markets’ report, Africa – Mobile Voice and Data Communications Statistics).

More mobile numbers

Other trends and learnings in the Africa –Mobile Voice and Data Communications Statistics report include:

- The growth rate in connections in sub-Saharan Africa has been especially impressive in the past 10 years, outpacing that of other developing regions and outstripping developed regions by far.

- Certain mobile services, such as 3G, have grown by nearly 50% each year.

- An estimated 90% of all phones in Africa are mobiles, meaning mobile operators provide an alternative for poor and absent fixed-line telephone infrastructure.

- Mobile network operators serve as primary internet service providers.

How mobile impacts the African economy

The African continent has some of the highest global levels of mobile internet use. That’s according to the Groupe Spéciale Mobile Association(GSMA) Sub-Saharan Africa Mobile Observatory, a monitoring initiative based on research by Deloitte.

In countries like Zimbabwe and Nigeria, mobile Internet accounts for over 50% oftotal web traffic, while the global average is more like 10%.

Naturally, numbers like this have spawnedthe development of an array of commercialendeavours around mobile, according to Jon Hoehler, head of mobile at Deloitte & Touche in Johannesburg.

These endeavours feed into various sectors and services, including:

- 1 airtime sales

- 2 mobile advertising and value-added services

- 3 agricultural services

- 4 education

- 5 health system tools and services

- 6 banking

“Banking in particular has benefitted with mobile providing a platform for the rollout of mobile-based banking products for the unbanked and those in remote areas,” says Hoehler. As a result, he explains, the rate of mobile proliferation throughout the continent has had a huge economic impact and will continue to do so for a while yet, albeit at a slower rate.

Evidently, “huge” is not an overstatement.In 2011, GSMA figures put mobile’s direct contribution to the sub-Saharan economy atUS$ 32-billion, or 4.4% of GDP.

In the same year, the mobile sector created more than 3.5-million full-timeequivalent jobs in the formal and informalsectors, and yielded US$ 12-billion intaxes for governments in the region.

Another Deloitte report estimatesthat a 10% increase in mobile phone penetration can be linked to a 1.2% GDP increase in a middle or low-income country. Why?Because increased connectivity leadsto increased economic activity. Clearly mobile can help to boost both the earning and spending of money.

Apps for Africa and mobile-inspired economics

Consider M-Pesa, the UK-funded, Kenya-developed mobile banking solution that’s been hailed as a model for financial inclusion. Run by mobile operator Safaricom, M-Pesa’s latest figures indicate that, with cellphone in hand, about half of Kenya’s 43-million people use the service to send money, pay bills and withdraw money at registered agents around the country.

It’s a clear example of African mobile innovation success – as well as of how mobile can enhance economic activity. Now Safaricom, working jointly with the Commercial Bank of Africa, has extended M-Pesa’s product offering to include M-Shwari, a loan service that has the potential to further grow the spending prowess of Kenya’s growing middle class.

With so many people and phones and growing disposable incomes, it’s no wonder that Africa is becoming something of a destination formobile tech. Director of the Harvard Science, Technology and Globalisation Project, Professor Calestous Juma, says that Kenya’s nascent Nairobi-centred tech sector – which began as a collective of tech-savvy bloggers – is a test case that’s spurred investment in other hubs in South Africa, Nigeria, Madagascar, Botswana, Uganda and Cameroon, among others.

It is this unrestricted, innovation-rich environment that birthed tools like M-Pesa and Ushahidi, a Kenyan crowdmapping platform that’s garnered global praise for its simplicity, flexibility and social power, particularly when used during a crisis, such as the 2007 Kenyan election when it was created to collate email and SMS reports of violence on Google maps.

Then there’s Konza, or “Silicon Savannah”, a US$ 14.5-billion tech city 64km south of Nairobi that the Kenyan government began building early in 2013. The aim is to provide an attractive space for global tech companies to set up base and help spur the revolution.